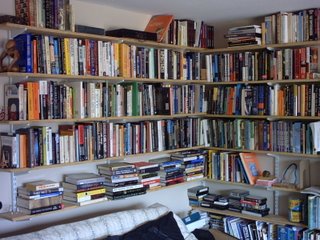

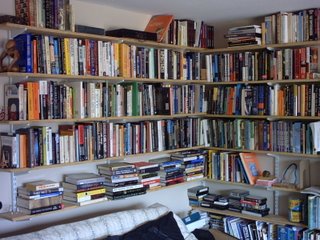

John Smart in the Library of Babel

Whenever John Smart visits I am curious which of my books he will look at. I collect books on history, technology, science, sociology, politics, philosophy—anything to help me understand how the Universe works—at a much faster pace than I read. My collection is not as large as Jorge Luis Borge’s Library of Babel, which includes all books that could be written, but I’m working on it.

With so much treasure at hand, I am limited by time and my reflexive desire to luxuriate in the ideas (rather than skim). Smart is visiting this weekend for the Foresight Conference, so I am tempted to invisibly spray my bookshelves so I can return with a blacklight (or other magic from CSI) to trace his path through my books.

The Second Curve: Managing the Velocity of Change by Ian Morrisson was pulled from the shelf. That fits with our conversation about experience curves from Kurzweil’s The Singularity is Near, developing a graduate program in “technology roadmapping,” and Future Salons in high schools and eventually middle schools to prepare young people to think about the future in terms of decades and more. Technology roadmapping is an approach to planning that combines scenario “what if” techniques with technology trends “what probably will be” (S-curves and exponential curves from The Singularity is Near).

The graduate program could first appear at the forward-looking University of Advancing Technology, and I see a possible connection with the Information Systems Management program at UCSC, newly directed by KnowledgeContext advisor Suresh Lodha. ISM, renamed ISTM to include technology, has an undergraduate program and is developing a graduate one. At the high school level, he pointed me to an existing foresight development program in many high schools across the country: the Future Problem Solving Program.

The Santa Cruz Future Salon is nearing birth. I’ve been meeting with the newly-formed Santa Cruz Futurists, a UCSC student group. This university and this region have many thoughtful, foresightful, brilliant people I’d like to interact with. It will be good to have a locus. Connecting back to high schools, the UCSC group showed interest in eventually helping local high schools form their own Future Salons.

With so much treasure at hand, I am limited by time and my reflexive desire to luxuriate in the ideas (rather than skim). Smart is visiting this weekend for the Foresight Conference, so I am tempted to invisibly spray my bookshelves so I can return with a blacklight (or other magic from CSI) to trace his path through my books.

The Second Curve: Managing the Velocity of Change by Ian Morrisson was pulled from the shelf. That fits with our conversation about experience curves from Kurzweil’s The Singularity is Near, developing a graduate program in “technology roadmapping,” and Future Salons in high schools and eventually middle schools to prepare young people to think about the future in terms of decades and more. Technology roadmapping is an approach to planning that combines scenario “what if” techniques with technology trends “what probably will be” (S-curves and exponential curves from The Singularity is Near).

The graduate program could first appear at the forward-looking University of Advancing Technology, and I see a possible connection with the Information Systems Management program at UCSC, newly directed by KnowledgeContext advisor Suresh Lodha. ISM, renamed ISTM to include technology, has an undergraduate program and is developing a graduate one. At the high school level, he pointed me to an existing foresight development program in many high schools across the country: the Future Problem Solving Program.

The Santa Cruz Future Salon is nearing birth. I’ve been meeting with the newly-formed Santa Cruz Futurists, a UCSC student group. This university and this region have many thoughtful, foresightful, brilliant people I’d like to interact with. It will be good to have a locus. Connecting back to high schools, the UCSC group showed interest in eventually helping local high schools form their own Future Salons.